If the vast majority of high school students today pass the baccalaureate, this democratization of schools goes hand in hand with new inequalities in the choices of sectors and pursuits of study.

Just 40 years ago, Jean-Pierre Chevènement, then Minister of National Education, set the cap of leading 80% of an age group to the baccalaureate. Today, this objective has been achieved, and even exceeded, which has mechanically led to a democratization of higher education.

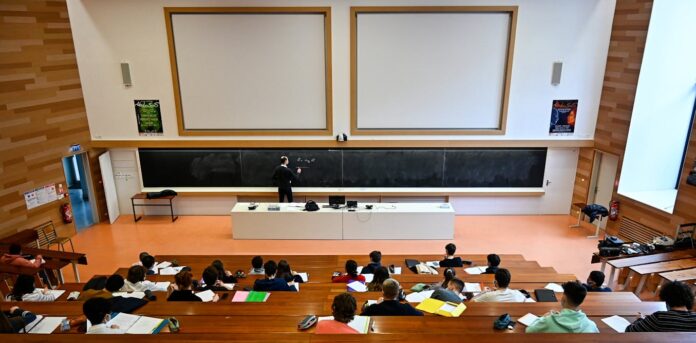

Over the same period, in fact, the numbers enrolled in higher education increased from a little over a million to three million. This tremendous movement to open up a space that has long remained the prerogative of the dominant classes can be explained by a certain number of proactive policies. Thus small and medium-sized universities developed in the 1960s, then sections of higher technicians (STS) and university institutes of technology (IUT) which today welcome a fifth of students, the university by welcoming one in two.

However, these figures are not only due to policies, they are also due to the increase in the level of aspirations of the population which cannot be limited to a single logic of employment.

Whether it is a sign of social distinction like the great international schools for privileged class families or “the weapon of the weak” specific to working families, the aspirations of higher education are also part of the long perspective of the history of the job market, social classes and families.

The professional sector has widened access to the baccalaureate

Observed in detail, this democratization nevertheless reveals important lines of division ultimately reflecting what the sociologist Pierre Merle calls a segregative democratization. That is to say that socio-academic recruitment differs between training courses, which are both unequally profitable and unequally valued as emphasized by Marie-Clémence Le Pape and Agnès van Zanten.

If today we cannot deny that the duration of schooling continues to lengthen for more and more young people, we can nevertheless question the variations in the duration of studies. This makes it possible to capture inequalities in access to higher education and diplomas. By tracing the thread of this segregation, we see that it is the product of a complex process combining educational policies and the aspirations of the population.

Although the increase in numbers was initially driven by post-war demographic dynamics, it was mainly the expanded access to the baccalaureate linked to a diversification of the offer – notably through the professional baccalaureate (1985) led by J.-P. Chevènement – which contributed to the increase in the proportion of high school graduates in a generation, and therefore to the increase in the number of new high school graduates enrolling in higher education.

While this rate has remained relatively stable for around ten years (around 78%), figures from the Ministry of Higher Education (2024) show that, although inequalities in access have decreased, they nevertheless persist. We first note that the rate of continuation in higher education has an upward trend for all social categories.

Among young people aged 20 to 24, 52% of the children of workers or employees are studying or have studied in higher education, compared to 77% of the children of managers, intermediate professions or self-employed people (i.e. a difference 1.5 times between the two groups). This same gap is 1.9 for people aged 45 to 49 (33% versus 62%), which clearly suggests democratization in progress.

More or less long studies depending on the baccalaureate series

However, we note the persistence of inequalities regarding the duration of studies. The continuation rate varies mainly depending on the baccalaureate route. While nearly 93% of general baccalaureate holders are pursuing it and nearly 81% of technological baccalaureate holders, vocational baccalaureate holders are only at barely 46%.

This disparity in pursuit is also found in the type of higher education sector. By considering a dividing line between short professional higher education and long general higher education, there appears a high prevalence of socio-academic origin in access to higher education. While 50% of general baccalaureate holders enroll immediately at university, technological and professional baccalaureate holders are 14% and 4% respectively. Conversely, the first 9% to enroll in STS, compared to 40% and 39% for their peers.

Shutterstock

The most prestigious courses, which are the preparatory classes for the Grandes Écoles (CPGE), although they concern barely 6% of new baccalaureate holders, have constituted for 20 years a privileged indicator for studying the democratization of higher education. However, despite policies of social openness, this sector continues to mainly concern general baccalaureate holders since they represent nine out of 10 students and the majority of students from well-off families who represent 52% of students compared to 7% of children from workers, highlighting both the failure of policies and the maintenance of a segregated space even in the grandes écoles.

A democratization that particularly benefits the wealthy classes?

Generally speaking, we can see a democratization since between 2011 and 2021, the share of 25-29 year olds holding a higher education diploma increases from 42% to 50% (+8 points). However, while it goes from 58% to 66% (+8 points) for the children of managers and intermediate professions, it goes from 30% to 33% (+3 points) for the children of workers or employees. .

Looking more specifically at the type of diploma, we see that in 2021, 41% of the former obtained a master’s degree, a doctorate or a high school diploma (+18 points compared to 2009) while the latter are only 13 % in this case (+ 7 points). So the proactive policies which have favored access to higher education seem to have mainly benefited the most advantaged categories who distinguish themselves by long, valued and profitable studies.

(Already more than 120,000 newsletter subscriptions The Conversation. And you ? Subscribe today to better understand the world’s biggest issues.)

If Parcoursup wanted to put an end to this “insider trading” seeming to be based on informational capital, by proposing a generalization of access to information to the 13,900 training courses present on the platform, it appears that this does not has done nothing about socio-academic segregation.

Recent work on the subject highlights the very heterogeneous implementation of this procedure within secondary schools and superior. This heterogeneity prolongs the inequalities of the orientation process at the heart of which educational policies and the aspirations of the population do not form the virtuous circle that the promoters of rationalized access to higher education defend.

On the contrary, it ultimately results in socio-academic segregation and, later, unequally profitable higher education. as Pierre Courtioux has already shown about “the lowest returns for graduates of “low” working-class origins.