As a consequence of global warming, rising sea levels particularly threaten certain territories in the Pacific. Participatory science programs are set up to monitor coastal developments as closely as possible, with the support of local populations, and adapt public policies.

During the last Pacific Islands Forum summit in Tonga which took place at the end of August 2024, the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres launched a “global SOS” on one of the direct consequences of global warming: the rising water levels in the Pacific.

Mr Guterres notably recalled recent research work showing an increase faster than the world average in certain areas of the Pacific. Many territories, made up of atolls and low-lying islands, are already strongly threatened by coastal erosion, marine submersion of low-lying areas or even the salinization of coastal aquifers and all of its corollaries (reduction of drinking water, loss of agricultural productivity of traditional food crops, etc.).

With 50% of the Pacific population living within 10 kilometers of the coast and more than 50% of their infrastructure concentrated less than 500 meters from the latter – proportions which increase each year – the vulnerability of the coasts will continue to be exacerbated in the near future.

To deal with this observation, shoreline monitoring then makes it possible to analyze the morphological evolution of the coastlines by identifying the processes of erosion and accretion, that is to say retreat or advance of the feature of side. This is the prerequisite for a better knowledge of coastal dynamics and therefore for effective management of the coastal area.

Monitoring the coastline helps inform public policies and the implementation of development, protection and coastal risk reduction measures in problematic areas.

How to measure the dynamics of the coastline?

To analyze the evolution of the shoreline, the frequency of which can be multi-year, annual, seasonal or event-driven, several methods and techniques can be deployed (pp. 270-277). We will cite for example:

-

geomorphological and sedimentological field observations;

-

diachronic mapping from aerial photographs and/or satellite images by visual interpretation of the position of the coastline;

-

or the temporal analysis of topo-morphological surveys.

The latter are obtained in particular by cutting-edge technologies such as GNSS (geolocation and navigation by a satellite system) or by means of a LIDAR sensor (a process which uses laser beams to measure distances). Embedded on a plane or a drone, this type of sensor makes it possible to produce very precise 3D representations (called digital terrain models) of the morphology of sandy beaches.

The acquisition of topographic data can also be carried out in a much more basic way using the “topometer frame”.

The Duff, 2015

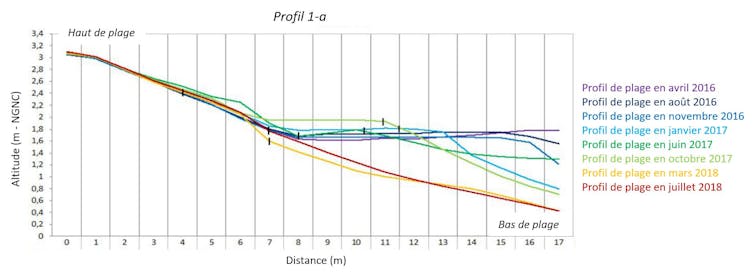

This is a robust, reliable, low-cost and easy-to-use sliding board device. This aims to measure a difference in altitude between two points for the development of beach profiles, that is to say graphic descriptions of altitude variations, along an axis perpendicular to the beach.

The comparison of successive profiles surveyed from the same reference point, on different dates, makes it possible to determine the evolution of the shoreline, by characterizing the phases of erosion, accretion or stability. This tool is adapted to the island context with sandy coasts with soft topography and relatively narrow with a length of less than a hundred meters for easy creation of profiles.

Why implement a participatory approach?

The participatory approach, also called participatory or citizen science, is a research approach that involves the public in the collection and production of scientific knowledge.

As part of our shoreline monitoring research programs carried out in New Caledoniain French Polynesia or Vanuatu, local populations actively participate in the collection of field data. Involved in particular are residents of the study sites, schoolchildren, associations and even the technical services of town halls.

After having been trained in the use of the topometer frame, these actors independently take the topographical measurements necessary to produce the beach profiles, which are subsequently transmitted to the scientific teams for analysis.

In the Loyalty Islands in New Caledonia, for example, customary lands are governed by rules and traditions specific to local communities. In addition to guaranteeing access to these spaces for study areas, the participatory approach makes it possible to obtain regular measurements or after the passage of an “extreme” meteorological event such as a depression or a tropical cyclone. These measurements, which are difficult to capitalize on by scientists alone, make it possible to populate a database and thus build a participatory coastal observatory.

Beyond the acquisition of data, the association of local communities allows us at the same time to carry out awareness-raising and training actions, in particular through workshops aimed at school audiences, oriented around the vulnerability of beaches, the prevention of coastal risks or even issues linked to the rise in sea levels.

J. Daniellot-Dejoux 2023

Particular attention is paid to the issue of climate change because various studies have shown that, for the populations of small island states in the Pacific, this topic is not always considered a major concern. Indeed, the responsibility and therefore the resolution of the consequences of global warming are above all those of the Western and Asian powers, the main emitters of greenhouse gases.

These environmental education initiatives are then, for example, an opportunity to become aware of the danger represented by certain local practices, such as sand removal, or coral blocks on reef flats, too often used for the construction of homes with as direct consequences the acceleration of coastal erosion.

J. Peinaud, 2023

The participation of local populations also allows for a better understanding of the socio-cultural functioning of the study area, particularly that of the coastline and the rules of use associated with it. Thus local knowledge is collected and integrated into management and development projects such as nature of environmental changes over timeindigenous knowledge and techniques and local coastal management practices, the representations and perceptions that users of their coastline may have or even the protection and adaptation measures implemented on the shores.

All of these contextualized elements aim to bring “resident knowledge” and “expert knowledge” of researchers into dialogue, an essential approach to effective coastal management adapted to local contexts.

By directly involving local communities, rather than being imposed on them by an approach top-downour research programs benefit from better legitimacy and acceptance as well as stronger ownership, a guarantee of greater sustainability. This is particularly important in Oceania, where island communities can be isolated and self-reliant.

Ultimately, the participatory approach combining training, data collection and awareness-raising makes it possible to co-construct adapted solutions and local strategies based on direct experience of impacts and knowledge of the environment of local communities for better planning of the environment. adaptation to climate change.

This article is published as part of the Science Festival (which takes place from October 4 to 14, 2024), and of which The Conversation France is a partner. This new edition focuses on the theme “ocean of knowledge”. Find all the events in your region on the site Fetedelascience.fr.