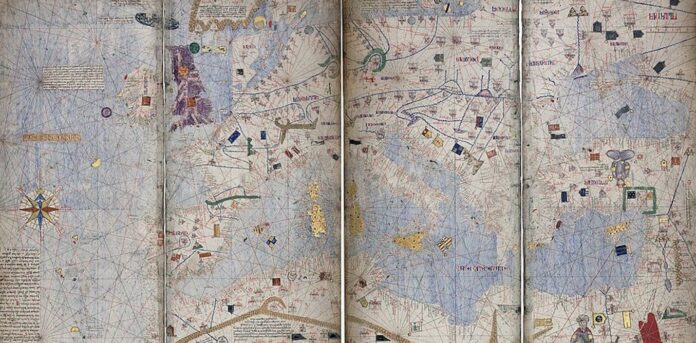

In the West, the Middle Ages saw the flourishing of richly ornamented nautical charts. But alongside these ceremonial maps, notarized archives reveal the existence of nautical charts intended for sailors, which described the coasts by listing the ports, the distances and the main difficulties and obstacles to be avoided. Located at the crossroads of routes and constituting essential stopovers for navigation, the Mediterranean islands occupy a central place in these representations of maritime space.

The last centuries of the Middle Ages saw the birth of Western nautical cartography. Thousands of nautical charts, produced in the main ports of the Western Mediterranean (Pisa, Genoa, Venice, Majorca) are thus preserved in the main European libraries. Appeared in the 13th centurye century, at the same time as the compass and the progress of offshore navigation, these maps combined the empirical knowledge of sailors, who practiced navigation by dead reckoning, the geographical knowledge of scholars, and the know-how of painters.

In the XIVe and XVe centuries, more and more richly decorated, numerous nautical charts came to decorate the royal and princely libraries. Produced in 1375 by the Majorcan Jew Abraham Cresques, cartographer of the King of Aragon Peter the Ceremonious, the Catalan Atlas is one of the most beautiful illustrations of this medieval geographical culture.

However, alongside these ceremonial maps, notarized archives reveal the existence of nautical maps whose use can be linked to the “portulans”, a sort of road maps intended for sailors, which described the coasts by listing the ports, distances and the main difficulties and obstacles to overcome.

Provided by the author

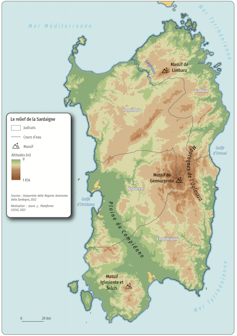

Located at the crossroads of routes and constituting essential stopovers for navigation, the Mediterranean islands occupy a central place in these representations of maritime space. The study of nautical charts thus opens the question of medieval representations of islands. In this perspective, we will be particularly interested in the Tyrrhenian area, focusing the analysis on the Corso-Sardinian archipelago.

Corsica and Sardinia on nautical maps in the 13th and 14th centuries

Provided by the author

The Pisan Map (late 13th century) constitutes the first known representation of Corsica and Sardinia. Inscribed perpendicular to the coastlines, the toponyms provide us with information on the main maritime outlets of the two islands. In red are the real ports while in black are the secondary stops.

Three ports are therefore identified: Bonifacio located in the extreme south of Corsica, and only around ten kilometers from the north of Sardinia; Oristano, in west-central Sardinia; Cagliari in the south-east of Sardinia.

A strategic key to Tyrrhenian navigation, the Pisan port of Bonifacio was conquered by the Genoese in 1195. As the Corsican chronicler Giovanni della Grossa (1388-1464) points out, the capture of Bonifacio was aimed at strengthen Genoese domination in northern Sardinia.

Provided by the author

An important notarial collection, dating from the 13the century, reveals that the commercial area of the city extended over the two islands. Bonifacio was thus at the center of a triangular trade linking Genoa to Corsica and Sardinia. Genoese merchants bought the products of island agriculture (cereals, hides) and sold the productions of Italian crafts (sheets, ceramics).

Provided by the author

Furthermore, due to its strategic position, Bonifacio was one of the centers of the Mediterranean Corso-Piracy. In Sardinia, Oristano and Cagliari constituted the two port outlets of the rich Campidano plain. The cereal production of this plain, higher than the needs of an island characterized by chronic underpopulationfueled trade with Genoa, Pisa and Barcelona.

Provided by the author

In 1297, the creation of the kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica by Pope Boniface VIII, and its subservience to the sovereign James II of Aragon, endowed the islands with a new political unity. However, if the conquest of Sardinia began in 1323, it was not completed until 1409, while Corsica never became Aragonese. In the 14the century, the Corso-Sardinian strait turned into a space of war between Genoa and the Crown of Aragon, for the domination of the islands and the sea. The evolution of cartographic representations of Corsica and Sardinia could be a distant reflection of this.

Provided by the author

On the map by Angelino Dulcert, produced in Majorca in 1339the banners seem to indicate a theoretical border between a Genoese Corsica on one side and an Aragonese Sardinia on the other, which contradicts the legal notion of Regnum Sardiniae et Corsicae.

In contrast to the Aragonese royal claims, the cartographer, of Genoese origin, considered that Corsica fell under the domain of Genoa, due to its commercial domination. We also note that the toponyms are more numerous for Corsica than for Sardinia, for which only the main ports are mentioned: Alghero, Bosa, Oristano and Cagliari. This political-economic perception of the islands also emerges from the analysis of toponyms which appear in the Catalan Atlas. We indeed note the absence of the port of Bonifacio, which contrasts with the immense erudition demonstrated by this atlas.

Rather than an oversight, to the extent that we know that Cresques was based on Dulcert’s map, one would be tempted to see it as the expression of a choice: that of representing a “Catalan route of the islands “. Thus, in the north of Sardinia there is Longosardo (Santa Teresa di Gallura), a Catalan port located opposite Bonifacio, but not Castelgenovese (Castelsardo), the main Genoese port in the north of the island. which appeared on an earlier Genoese map. On the western coast of Corsica, the mention of Cinarca appears for the first time, eponymous fortress of Corsican lords allied to the King of Aragon. Overlooking the sea, this fortification made it possible to control navigation along the western coasts of Corsica, a route between Italy, Provence and the Maghreb. It was at the center of a racing activity, carried out, in the name of the king, by the Cinarchesi lords against the Genoese interests in the island.

Provided by the author

In 1375, Arrigo della Roccaadorned with the title of lieutenant of King Peter the Ceremonious, had himself proclaimed count of CorsicaCinarca thus became the political and military heart of the Aragonese “kingdom of Corsica”. Due to archival gaps and the absence of archaeological excavations, its economic role remains more difficult to grasp. Finally, it should be noted that unlike Dulcert, Cresques does not display any banners on the two islands, which could reflect the uncertainties linked to the war.

Islanders and first regional maps of the islands in the 15th century

After several decades of war, the mid-15th centurye century saw the establishment of a lasting peace between Genoa and the Crown of Aragon, which allowed the birth of Genoese Corsica and the consolidation of Aragonese Sardinia. This political evolution was contemporary with new cartographic representations of the islands, from the Islanders model.

In Corsica, these first regional maps reveal a new interest in the hinterland, which raises the question of the links between cartography and political domination. Made in Naples in 1511, the map of Corsica by the Genoese cartographer Vesconte Maggiolo is a beautiful illustration of this evolution of representations.

In order to represent the territory, the cartographer was forced to distort the contours of the island. In addition to the coastal information already present on the nautical charts, there are numerous vignettes of towns, manorial fortifications and village habitats. The memory of the Viceroy of Corsica, Vincentello d’Istriabeheaded in front of the public palace of Genoa in April 1434, seems evoked through the representation of its ancient castles dominating the Serra d’Istria: Buturetu. The definitive victory of Genoa against the Corsican and Aragonese “tyrants” is, however, remembered by the banners proudly brandished in the coastal towns: Bastia, Ajaccio and Bonifacio.

Provided by the author

The evolution of the cartography of the islands in the last centuries of the Middle Ages seems to reflect a change in their representation. First conceived as essential stopovers along maritime routes, the islands gradually became coveted territories, the conquest of which was seen as the key to economic and political domination of the sea.

This article is published as part of the Science Festival (which takes place from October 4 to 14, 2024), and of which The Conversation France is a partner. This new edition focuses on the theme “ocean of knowledge”. Find all the events in your region on the site Fetedelascience.fr.